How Stamford became the first Conservation Area

The Society's 2017 exhibition explains how and why Stamford became the first Conservation Area, marking the 50th anniversary of the town's designation. Click on any picture to enlarge it. Further down the page we have people's memories of Stamford and quotations about the town. Many of the pictures have been supplied by other people and organisations; the relevant copyright information is displayed alongside each image.

Memories of Stamford before 1967

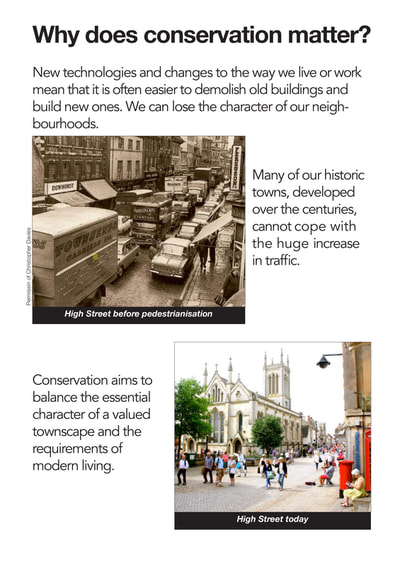

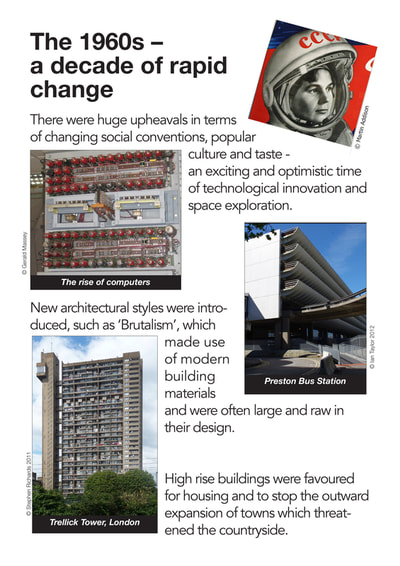

The town centre of Stamford may look more or less the same as it was in the 1960s, but many people remember it as a very different place. It served most of the day-to-day needs of local people. Independent shops from grocers and greengrocers to clothing and furniture shops have now been replaced by ‘high street’ stores typical of any town.

Many people lived in the centre of town ‘over the shop’ and this created strong communities which kept the town alive.

Some of the memories of life in Stamford, collected for the exhibition, appear below. More recollections of times past are available at Stamford Memories – Ancestor Gateway. You can also add your own memories.

Many people lived in the centre of town ‘over the shop’ and this created strong communities which kept the town alive.

Some of the memories of life in Stamford, collected for the exhibition, appear below. More recollections of times past are available at Stamford Memories – Ancestor Gateway. You can also add your own memories.

|

I am Stamford born and bred, growing up in Queen’s Walk, an area known then as the West End. Dr Till bought me into the world at Stamford Hospital.

My father, Harold, worked at the grocers T&J Eayrs in High Street (where Fat Face is now), as did I on some school holidays. He was first an apprentice then a traveller for the firm, collecting orders from people who lived in the surrounding villages and introducing them to new products. It was a splendid shop that sold a wonderful range of groceries including its own brand of tea and coffee. The business prided itself on personal service and was managed by brother and sister Cecil and Grace Eayrs who were Plymouth Brethren, an evangelical Christian movement. They were kind but had strict beliefs and did not mix with outsiders. I went to school first at St John’s infant school, on the corner of West Street and Scotgate. The headmistress was Miss Boosey, who only died a few years ago, and I thought that she was old in the 1940s! When I was 7 years old I moved to St Martin’s, the boys elementary school on the corner of High Street St Martin’s and Kettering Road, and ended my school days at Stamford School. It wasn’t always the good old days. Healthcare is much better now. When I was 6 years old I caught Scarlet Fever, then an extremely |

infectious and dangerous disease. I was bundled into a blanket and taken by ambulance to an isolation hospital in Bourne where I had to stay for 8 or 9 weeks.

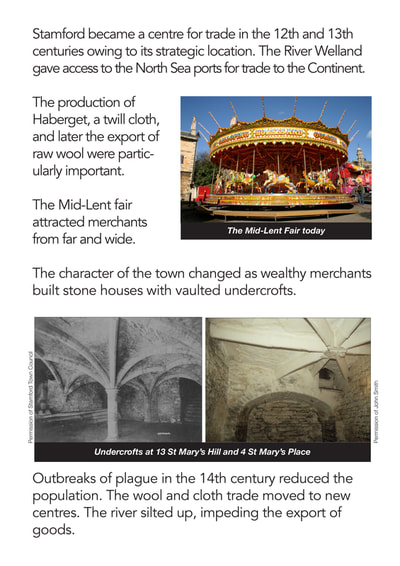

We children found lots of ways of entertaining ourselves – playing in the street, or on the Meadows. There was a big hump dividing the Meadows along the line of today’s footpath which was made from spoil when the castle mound was pulled down. This was pierced by two large pipes for drainage and we enjoyed wriggling through the pipes. The Mid Lent Fair used to take place where the Bus Station is now, and fairground folk would park their caravans on Bath Row. When we were in our teens in the 1950s we would arrange our own parties at the All Saints’ church hall in Foundry Road. We used to hire John Hillier – he ran an electrician’s shop in St George’s Street – as a DJ. He could provide a turntable and speakers and had a good collection of Rock & Roll. I was an early member of the Stamford Players and had great fun appearing in the pantomimes. Stamford was a small place then and everyone knew everyone else. People were expected to do things to support the community, from the professional business men to us boys. You were tapped on the shoulder and asked to help, and you did what you could. John Davies |

|

I grew up in the Cornstall Buildings, off St Leonard’s Street, which were attractive small houses built by the Newcombs who owned the Mercury. My grandmother moved into the house in 1898. One of the most exciting memories of my teenage years was duringWorld War II when a large German bomb whistled horizontally through number 17, causing a trail of destruction. Luckily no-one was seriously hurt – not even the householder Mrs Griffiths, who was sitting with her baby in the front room. We were all evacuated until the bomb was defused – it had been timed to detonate 96 hours later.

During the war there were lots of very effective emergency plans to cope if people were bombed out of their homes. The Fane School – where Stamford Welland Academy is now – used to hold supplies of food and bedding. The Town Hall kept large stores of clean, second-hand clothing. Stamford received quite a few evacuees at this time. Pupils from the Mundella Grammar School in Nottingham were evacuated to Stamford on the outbreak of war and returned to Nottingham in March 1940. The second group of evacuees came a bit later – they were pupils at Camden High School for Girls – known as the ‘green ies’ because they were seen all over town and wore a green uniform. They shared the facilities of Stamford High School. During the war years in the school holidays boys had to fill in by doing urgent jobs to keep things running. When I was 13 years old I was asked to help out with delivering telegrams when the people who usually did this were tackling the large amount of Christmas mail or on their holidays. This meant riding a heavy bike around Stamford and out into the sur- rounding villages, as far as Tallington and Essendine. We were paid 4 pence an hour, which added up to about £1.00 per week. I worked in the gas and electrical businesses for most of my life, starting out with East Mid- lands Gas on Wharf Road in the Weighbridge of ce. You can still see the weighbridge to- day, where heavy loads could be weighed. The site of the gasworks was where the Wharf Road car park is now, stretching down to the river. For the last 26 years of my working life I was in the gas show rooms in St Mary’s Street – where the Vacuum Store is now. People used the show rooms to buy new appliances, but also to pay bills and report problems. You got to know everyone and personal service was very important. After I married we moved to Foundry Road, where Blackstone’s Foundry had been prior to its move to the large Ryhall Road site. In those days there were lots of old cottages but these were compulsorily purchased by the Council in the 1960s and pulled down. They were judged to be in a poor state by Mr Roll, the Public Health Inspector, who was ruthless if he thought properties were unkempt and not clean. I don’t think this would happen these days as the cottages could have been renovated. Geoffrey Lawrance |

I lived ‘over the shop’ at 2/3 Maiden Lane which was owned and run by my grandfather from 1908 (previously the business had been in High Street) and joined by my father from 1946. F E Riley & Son was a drapers and outfitters that sold a wide range of products including gramophones, linoleum, and rugs were a speciality. Stamford was full of local shops and as a market town served the day-to-day needs of those who lived in the town and surrounding villages.

I grew up looked after, and led on, by my 5 brothers and we had marvellous places to play in and explore. There were the Meadows, where we swam in the river and in the winter of 1962/63 walked over the frozen river under the town bridge. Before Warrenne Keep was built there was a dilapidated area with big storage caverns cut into the Castle mound where we would hide out. The backs of gardens between Maiden Lane and St George’s Street could be climbed into and explored, as well as the derelict house next door. We had all the childhood diseases, but the Doctors’ practice was just down the lane and Mum could call Dr Till or Dr Mackie at any time if we were ill or had an accident. I always think that Stamford stones are in my bones! We drank the metallic tasting water from the old Iron Spa and local spring water – maybe this is one reason that both my father and grandfather lived into their 90s. I went to St George’s primary school (in those days it was where Old School Court is now, later in Kesteven Road), followed by Stamford High School. Each day we would walk home to dinner. We went to church at St George’s. My grandfather was in the choir there for 80 years and got a letter from the Archbishop commemorating this achievement. We did not get a TV until I was 12, but we could still see some favourite shows – we used to watch and lip read Dr Who through the windows of the TV shop in High Street. Before the Conservation Area was created developers tore the heart out of the Maiden Lane/High Street, St George’s Street/St George’s Square quadrangle when many buildings and their gardens were demolished and built over. The chaos and dirt during this time were horrible. What is the biggest difference between then and now? The sounds and smells were different. The side streets did not get much traffic and there were sounds of children playing. The smells of the shops were very distinctive, from a hot metal smell of the shop that sold lengths of piping to the perfume of fruit in greengrocers, and the sides of bacon in the grocers. The trees opposite our house in St Michael’s churchyard were wonderful. In the 1920s my grandfather had paid for two trees to be planted in the churchyard to shade the shop. I always remember the wonderful smell of the catkins from the large tree in Dr Mackie’s front garden. We could also see the stars clearly in the sky at night. Kate Riley |

|

I was born and brought up in Essex Road, which was then the end of town. There were lots of wonderful places where children could play and explore – the spinney, where the Bluecoat School is now, the piggery run by Mr Butcher, known as ‘Pam’ Butcher, and the brickyard quarries off Little Casterton Road. I could look out from my bedroom window and see farmland beyond Worcester Crescent.

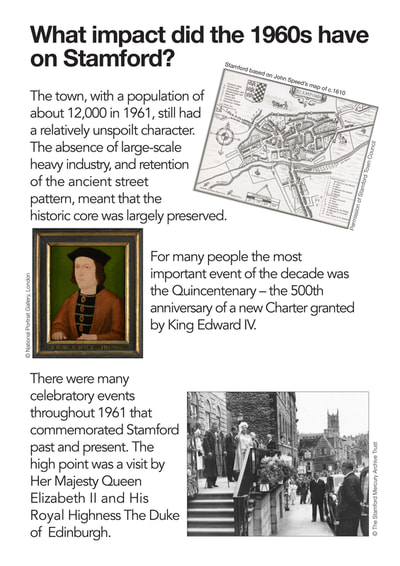

During the years of WW2 we commandeered one of the large local air raid shelters and turned it into a gang hut, as these were not used much as shelters. We would see lots of Italian prisoners of war who were building the foundations for the prefabs on Kings Road (which was a playing eld).They were very friendly and made wonderful children’s wooden toys which they sold to us. My favourite toy was a man on a string suspended between two sticks, which you could spin. Some things weren’t as pleasant. On the way home from St Augustine’s primary school in Broad Street, for lunch, we would look into the slaughter house - which was on the site of North Street car park - and see cows and pigs waiting to be killed. There were lots of different shops in town. Mr Johnson who ran the chemist shop on Red Lion Square was reputed to put iron water from the Spa (in Stamford Meadows) into his potions – and they worked! He was an eccentric and much loved man, and people preferred to go to him rather than the doctors. here were lots of other ‘characters’ we knew. The street cleaner, Bill Yates – known as ‘Ninny’ Yates was splendid – he was always there doing his job and knew everyone. When his funeral was held at All Saints’ Church there were huge crowds. ‘Nimpy’ Holmes was a tramp who used to stand outside the Library and hurl abuse at women passing by; he became famous for saving Lord Exeter’s horses when he spotted a fire in a barn on the estate. Lord Exeter used to let him sleep in a shed in the Park. We had two cinemas – the Central and the Corn Exchange – which were very popular; with queues down to Red Lion Square for the Central Cinema. We used to rush to see the advertising boards outside promoting next week’s programmes. There are many other highlights: the open air swimming pool, which was next to the Cattle Market - the unheated pool opened each year in March and the Mercury would take a picture of the first person who took the plunge; the Sunday afternoon concerts at the Recreation Ground bandstand, where loads of families would go and take picnics; football training on the Meadows, against the famous ‘hump’. One of the worst things that happened to the town was the demolition of the Albert Hall and adjacent buildings. Albert Hall was a central part of our lives – for weddings, parties, dances and talks. The site was sold off for money and it was not protected by the Council or any other group – what a pity! Philip Rudkin |

I have lived in and around Stamford for much of my life. My first job was for the engineering company Blackstone & Co., which had a large site off Ryhall Road. They were good employers and I enjoyed my time working there. You needed to be committed to your career and work hard – after a day in the Drawing Office I would go to evening classes at the Technical College in Broad Street to get my engineering qualifications. I used to ride my bike to work from where I lived in Stretton to Stamford, along the Great North Road – a round trip each day of 16 miles.

When I married 55 years ago I bought a house in Casterton Road. My children Julian and Jane used to play in the Williamson Cliff clay pits off Little Casterton Road – now disappeared and built over by housing. Stamford had many useful shops. I remember Harvey’s, the bakers on the corner of All Saints’ Street, the grocers in High Street and St John’s Street, Alfie Dexter’s petrol station in Scotgate. There were great places to play sports locally, such as rugby for the YMCA and I also played cricket at Blackstone’s pitch. I think that it is a pity so many houses are being built between Empingham and Tinwell Road, up to the A1. When this area was part of Rutland, before the A1 by-pass was built, we thought that it was important to stop the land being developed. In the 1950s I campaigned to keep Rutland independent, and although this did not happen it did become a separate district council within Leicestershire. I think that places with a distinct character, such as Rutland and Stamford, work best when they are run at a local level”. Walter Bunney, former Councillor for Rutland District Council and Chairman of the Planning Committee 1992-95 50 years ago how different Stamford was, most of the old stone buildings were the same, but not the way the town was run. Those days we had our own Borough Council, with local councillors and their officers making all the important decisions for Stamford.

Before we lost own rule our town was prosperous with plenty of employment in local factories etc. with names like Blackstones & Martin Markhams (engineers) Cascellords Ltd (plastics) Dolbys (printers and publishers) Doltoy Ltd (dolls’ furniture) Stamford Lime Company Ltd, Timber Mills, Godfrey & Company and Pledgers (steel) Gibson & Son (iron and brass foundries) William & Cliffs (brick works) also a very busy railway goods yard with 5 coal merchants all delivering in Stamford. In 1967 there were no supermarkets just friendly individual trade shops with 8 grocers, 4 ironmongers, 4 radio & TV, 4 tailors, 10 ladies & gentlemen’s out tters, 2 shmongers and many butchers etc. They all welcomed you into their shops with “Hello, can I help you?” Michael Lee |

|

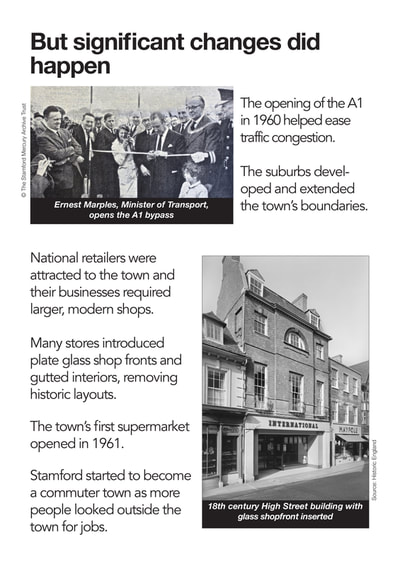

Stamford has changed in detail over the years, but is still a wonderful town. I remember lots of the old shops and places we used to visit, many now gone: High Street open to traffic; the three to four-storey brick grain store in the station yard; the wood yard; the ‘Seaton Flyer’; the ‘Dead Line’ siding in Uffington Meadows; the trestle bridge over the Welland and the old signal box nearby; the Stamford to Essendine line; Blackstone’s shunting engine and siding; car parking along the middle of Broad Street; the ‘Hump’ in the Meadows; the printers in Castle Street; the installation of the Stamford School bridge; Bassendines; Mac Fisheries; the wet sh shop in Red Lion Street; the seed merchant’s in High Street; Hart’s warehouse by the North Street chapel; Hawleys; Parker’s “Worthmore” store in High Street and their cat “Nimbus; ‘Ninny’ Yates; Burton’s; the snooker hall; Charlie Simpson’s cycle shop in Scotgate; old lorries dumped where Buildbase now is; the Camp off Empingham Road; Tim Garratt’s barber’s shop in Scotgate; Johnson’s butcher’s shops in St. Peter’s Street and Scotgate; the Bluecoat School in St. Peter’s Hill and its annex at the rear of the Methodist chapel “.

There always seemed to be a lot going on: the small dustcart with tiller steering; the drain-clearing lorry; the large dustcart whose body tipped to compact the load; the Albert Hall behind High Street where many events were held; Stamford School Speech Day services in St. Michael’s church; large lorries carrying concrete beams from Dow-Mac’s along High Street; the Katinka milk bar; ‘Newting’ in the brickyard ponds; swimming in the Gwash by the weir; the brick- yard light railway; Blackstone’s hooter; the re station siren; the 1962-3 winter; the long-gone pubs in the Town Centre. Councillor Max Sawyer, Deputy Mayor of Stamford 2017 |

I remember the euphoria after the tough years of World War II – the 1950s were a fresh start when things began to change. There was more money about to spend on exciting new fashions in clothes and music.

After leaving Stamford School I worked at the Stamford Mercury, which was still printed in town in those days. I was called up for National Service, which I enjoyed as it offered splendid opportunities to travel and learn new skills. The discipline of forces life encouraged us to be more tolerant. You had to share your life with many different people from all parts of the country. I liked the life and joined up, training to become a professional RAF photographer. It made me see Stamford afresh when I returned, and to value the traditions which gave the town a sense of place. RAF Wittering was given the Honorary Freedom of Stamford in 1961 and this is still celebrated every year in a special ceremony and parade through town of Service men and women. What do I miss from those days? Well I used to like travelling to Peterborough from the station in Water Street on the ‘coffee pot’, a local engine that pulled us to Essendine where you could change to the main line. Stamford was and is a very friendly place. There were lots of clubs and function rooms, now disappeared, including the Christobel Rooms, the RAFA club, now the Tobie Norris, and the quaint old Albert Hall. Before the Arts Centre was created the old theatre was a good place for jumble sales. There has been a lot of change over the years but Stamford is still special and distinctive. And not all change is bad - recent improvements to St Michael’s Churchyard and Red Lion Square have made these spaces more attractive and useable for everyone”. Councillor Tony Story, Mayor of Stamford 2017 |

Quotations about Stamford

|

For all the picture-postcard perfection of its 600 listed buildings (the 1994 BBC adaptation of Middlemarch was filmed here) or the water meadows that line the sparkling River Welland, our inaugural winning location remains a genuine and down-to- earth spot. A one-change rail route via Peterborough can see you at King’s Cross in an hour and a quarter, yet Stamford has been spared the hipster invasion - at caps are worn without irony here. Its pleasures tend towards the traditional.

The Sunday Times ‘Best Places to Live 2017’ |

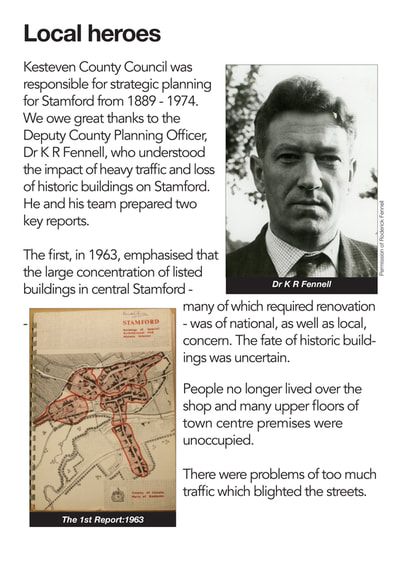

The deputy planning officer, Dr K R Fennell should have a statue or at least a plaque in Stamford. John Plumb, local historian, former Director of Leisure Services, Nottinghamshire County Council and Chairman of Stamford Civic Society, 1996-2007 |

|

“As fine a built town all of stone as may be seen... not very large but finer than Cambridge”. Celia Fiennes, an intrepid traveller, visited in 1697 |

The ducks are quacking and the river sparkles in the spring sunshine. Across the green of Stamford’s famous water meadows, young families and couples enjoy the day, sipping takeaway coffees from the cosy independent cafes, such as the Fine Food Store, that line the gloriously Georgian high street. It feels familiar — the town has starred in period dramas from Middlemarch to Pride and Prejudice, just one lucky by-product of Stamford being named Britain’s rst Conservation Area. The architecture and honey-stone streets really are magnificent, but that’s not all Stamford has to recommend it...

The Sunday Times ‘Best Places to Live 2013’ |

|

“If there is a more beautiful town in the whole of England I have yet to see it”.

W.G. Hoskins, ‘East Midlands and the Peak’, 1951 |

“Its mood is quiet; its colour mainly a pale buff-grey, reticent. But it has great dignity”. Alec Clifton-Taylor, in his book and TV series ‘Six English Towns’ |

|

“England’s most attractive town.” John Betjeman, poet and writer |

“When we were planning the programme we presumed we would have to film all over the country - a street here, a square there, a house somewhere else. But then our researchers came back and told us they had found this marvellous town that had everything. So I went up to Lincolnshire, took one look and knew they were right. Stamford is beautiful. Extraordinary. It’s absolutely stunning”. Louis Marks, BBC Producer of ‘Middlemarch’, 1993 |

Acknowledgements

The exhibition was generously supported by: Colemans; The George of Stamford; Institute of Historic Building Conservation; Historic England.

Stamford Civic Society would like to thank the following people and organisations that have helped us create this exhibition:

Mr David Baxter. Mr Roger Cullingham. Mr Christopher Davies. Mr David Ellis. Mr Roderick Fennell. Mrs Jean Orpin. Mr John Smith.

Colemans. The George of Stamford. Heritage Lincolnshire. Historic England. Institute of Historic Building Conservation. South Kesteven District Council. Stamford & District Local History Society. Stamford Arts Centre. Stamford Library. The Stamford Mercury Archive Trust. Stamford Town Council... and all the people who contributed their memories of Stamford in the 1960s.

Stamford Civic Society would like to thank the following people and organisations that have helped us create this exhibition:

Mr David Baxter. Mr Roger Cullingham. Mr Christopher Davies. Mr David Ellis. Mr Roderick Fennell. Mrs Jean Orpin. Mr John Smith.

Colemans. The George of Stamford. Heritage Lincolnshire. Historic England. Institute of Historic Building Conservation. South Kesteven District Council. Stamford & District Local History Society. Stamford Arts Centre. Stamford Library. The Stamford Mercury Archive Trust. Stamford Town Council... and all the people who contributed their memories of Stamford in the 1960s.

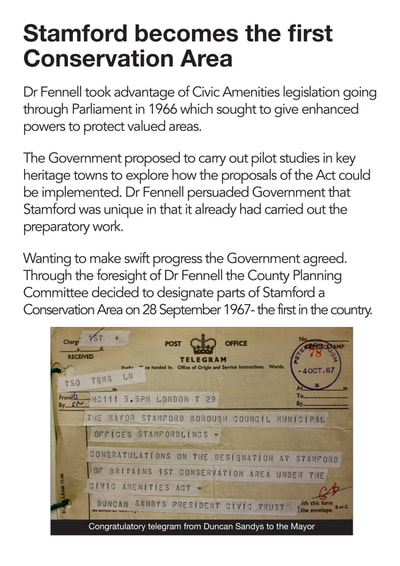

![The Civic Amenities Act introduced the concept of Conservation Areas, and was widely supported by the Government and all political parties.

In a House of Lords

debate in May 1967 Lord Jellicoe, representing the Conservatives, said that, “I should like to suggest that he [Mr Duncan Sandys] has probably done as much as any other English politician of his day, with the possible exception of Lord Silkin, to improve the visual quality of our country.

This Bill is undoubtedly the offspring of his rugged loins, and I am delighted to acknowledge its paternity”.

The Bill became law when the Civic Amenities Act was granted Royal Assent on 27 July 1967.](/uploads/1/2/9/9/12990/panel-22-june.jpg)