Harry Burton

|

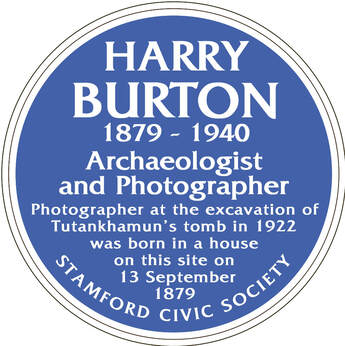

Harry Burton, the fifth child of eleven of journeyman joiner/cabinet maker William and Annie Burton (née Hufton) was born at 18 Burghley Lane, Stamford, on 13 September 1879. He was baptised at St. Martin’s Church on 15 October 1879 as Harry, not Henry, as he often appears on later documents. Before 1891, the family moved to 5 Church Lane, (renumbered as 21 Church Lane).

He started at Stamford St. Martin’s Church of England School, [Stamford High School Music School now], on 1 May 1883, seemingly leaving in 1893 [past the statutory age of 11]. Certainly by September 1883, 14 year old Harry was employed at the home of 32 year old Robert Henry Hobart Cust at 42 St. Paul’s Street, Stamford. Robin, as his family usually called him, came to Stamford about 1893 to help his cousin, Belton Estate heir, Henry John Cockayne Cust, who was standing as M.P. for the Stamford Division. |

On 26 September 1893 a nameless page boy is reported to have set fire accidentally to bedroom furnishings while chasing a cat which had caught a mouse! In a 1914 letter, Harry himself mentions that he was a page boy for Cust, who surprisingly didn’t dismiss Harry. Over time, Harry took on new roles in the household and was accepted as an equal in society.

Nowhere in letters in later life does Harry say how he made the leap from page boy to secretary. Next door neighbour and Cust’s friend, David Bloodworth, with a family-run commercial training school at 13 St. Paul’s Street, may have given guidance.

Robin was active throughout 1893 and 1894 in Stamford, but only had an allowance at his disposal. His father despaired of his spendthrift son, but paid off his debts. Harry must have known his employer had money problems, yet he stayed with him.

Out of the blue, Robin inherited a house in Barmouth, Wales, and some investments. Robin and Harry vacated No. 42, around March/April 1895 to visit Italy, prior to settling in Barmouth.

Harry Burton never lived in Stamford after 1895, but he visited and corresponded with family members in Stamford and elsewhere, throughout his life.

They left Barmouth behind around the end of 1896, to live in Italy. Cust was gathering information to expand his interest in Italian Renaissance art history, and was part of the Siena set. Teenager Harry took up photography for Robin’s work. Such was his talent that other art historians became his clients.

Cust began a book about painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi in 1897, which was published in 1906. Many of the well-respected Alinari Brothers’ photos of paintings were used, but also three of Harry’s. The preface gives information about Harry’s social position and work ethics…. traits evident in his later Egyptian times. ‘Finally, I have to thank, with all due appreciation and gratitude, my patient painstaking secretary and companion, Mr. Henry Burton, [sic], whose share of the labour, physical, mental and mechanical, entailed in collecting material and preparing it for the press, has been no light one’.

Robin and Harry were well-known for hosting art and literary gatherings, in their apartment overlooking the Arno on the Via dei Bardi in Florence from 1897 onwards.

Robin met American-born widow Cornelia Octavia Peacock (née Haggerty) in Florence, and they married in London on 25 October 1906. About 1910, Robin and Cornelia moved permanently to Vernon House, 13 Lyndhurst Road, Hampstead. Harry, who spent some time there, often referred to it as the Camden house.

In Florence, Harry became very friendly with American Theodore Davis, who held the concession to excavate in the Valley of the Kings from 1903 to 1914 and Davis took Harry to Egypt. Italy was a stepping stone to Egypt, where the climate only permitted excavation from November to April.

In 1912 Harry became Theo’s Director of Excavations and he worked on the mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu, as well as other sites. Poor health meant Theo gave up his excavation concession in 1914. Theo asked his friend Albert Lythgoe, first Curator of Egyptian Antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to employ Harry. He was assigned to make a thorough photographic recording of the monuments around ancient Thebes, where the Museum Egyptian Expedition had a permanent base. Then he was hired to record the work of the Museum’s

excavation team. Harry now worked for, and was paid by the MMA for about 25 years. Lord Carnarvon, who took over the concession from Davis in 1914, funded Howard Carter, but not Harry Burton.

34 year old Harry married divorcee Minnie Catherine Young, (née Duckett), on 18 July 1914, at Chelsea Registry Office, having met her in Italy, and where they now set up home. On the certificate, he describes himself as ‘archaeologist’. Cust bitterly resented the fact that Harry had made a life for himself working in Egypt and had married a divorcee. He had wanted Harry to give up Egypt, return to London and live like an English gentleman!

From 1916 to 1918, as a volunteer, Harry carried out war work in Cairo, mainly as the Assistant Director of the Re‐registration of Enemy Aliens!

While working for the Met., Harry accidentally stumbled across the Meketre tomb at Deir el Bahri in February 1921. His torchlight picked out the entrance through a crack in the rocks. Herbert Winlock who had been clearing rubble nearby, then took over.

So by 1922 when Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, Harry was an experienced archaeologist and photographer. Howard Carter often used his own photos and watercolour paintings to record his finds, but in his diary for 25 November he writes ‘Noted seals. Made photographic records, which were not, as they afterwards proved, very successful.’ He continued to give detailed daily written accounts. Albert Lythgoe, when asked for the loan of Harry’s services from the Met’s Theban base, willingly agreed. No excavation could take place until photos were taken. Harry later stated that Theo Davis had been only about six feet from discovering Tutankhamun’s tomb when he gave up in 1914!

Even more surprising, the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb on 26 November 1922 was never photographed. Harry Burton started work on 18 December 1922 photographing this so-called ‘untouched’ antechamber of the tomb. In fact it had been open for several weeks, and fitted with electric lighting, mirrors, and other devices to try to get the best photos. For a darkroom, to develop his plates, Harry used a nearby tomb, already a storeroom.

Lord Carnarvon sold the exclusive publishing rights with the photos to the London Times. Harry Burton’s first photographs appeared on 30 January 1923. But Egypt was politically unstable as Britain hadn’t yet given Egypt full independence. Howard Carter also clashed with the authorities on a personal level and closed down his excavations until 1924. Work then continued, Harry meticulously photographing and making notes on all the marvels from the tomb for ten years! The majority of those marvels stayed in Egypt as star exhibits in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum in central Cairo.

Preserved in the Oxford Griffith Institute is Minnie Burton’s diary, dating from 4 May 1922 to 20 October 1926. Among daily records of social and noteworthy events, are notes about the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb. She details such as their Florence life, their stays mainly in Luxor and Cairo, and various European holidays. The Burtons only visited New York once, in 1924. Edward Harkness, a Standard Oil Company millionaire and patron of the Egyptian Expedition funded their cross-country trip to California. He encouraged Harry to visit Hollywood to learn about a motion picture camera for the museum’s work in Egypt. Harry discovered the necessary set-up wasn’t suitable for his work. He later acquired a movie camera, but preferred to use his Sinclair Una camera, either handheld or on a tripod.

While Harry was working on Tut’s tomb, he was also ‘in free time’ doing jobs for the Met’s Theban

Expedition, and being seconded to other people’s excavations! By the late1930s, he had operations for health problems and long periods of recuperation. He also developed diabetes. According to the 1939 Register of 29 September, the Burtons were staying in Seal village, Sevenoaks, Kent. So war had already been declared. They returned to Egypt, as Italy was too unsafe. On 27 June 1940, at the American Mission hospital at Asyut, about midway between Luxor and Cairo, Harry died. Minnie stayed at his bedside until the end. ‘I felt so entirely lost without him’. Harry is buried in the American Cemetery in Asyut.

September 1943 saw allied bombs flatten 25 Via dei Bardi, Florence, destroying any records Harry kept there. Luckily Minnie was still absent.

Harry Burton has left a great legacy. It is estimated he made the Met. 7,500 excavation negatives, 3,345 of Theban monuments and tombs, 1,400 of Tutankhamun excavations, (one set in New York, and a slightly different one in the Oxford Griffith Institute). In Cairo and Italy, there are some 600 of Egyptian antiquities. His correspondence files are at the Met.. Between 1910 and 1940, he recorded over ninety Theban graves!

Harry was known for his modesty, charm, and dry wit, but above all, common sense. An executor for Carter’s Will, Harry advised Howard’s niece Phyllis Walker about a destination for his papers. In the few group photos of him, Harry is usually at the back, dressed in his ‘trademark’ plus fours, (like those of Theo Davis!). He sent expensive presents back to his relatives, and even paid for one nephew to go to Stamford School (until the lad’s father objected and withdrew him!) A niece and another nephew had passed the entrance exams around that time, so proving Harry was a fan of equal opportunities? Amusingly, Harry is said to have ordered British-made suits from Cairo, and they arrived addressed to His Excellency Burton, Tombs of the Kings, Luxor!

Harry’s shots are renowned for their clear tonal, shadowless definition. They tell a story, being much more than clinical scientific records. They are still used today to set up exhibitions which show precisely where objects were found over a century ago.

Harry Burton doesn’t get the credit he deserves. He achieved much more than being known as ‘the man who shot Tutankhamun.’ It is only right that Stamford honoured Harry Burton in June 2022 with a blue plaque on the site of the house of his birth.

Nowhere in letters in later life does Harry say how he made the leap from page boy to secretary. Next door neighbour and Cust’s friend, David Bloodworth, with a family-run commercial training school at 13 St. Paul’s Street, may have given guidance.

Robin was active throughout 1893 and 1894 in Stamford, but only had an allowance at his disposal. His father despaired of his spendthrift son, but paid off his debts. Harry must have known his employer had money problems, yet he stayed with him.

Out of the blue, Robin inherited a house in Barmouth, Wales, and some investments. Robin and Harry vacated No. 42, around March/April 1895 to visit Italy, prior to settling in Barmouth.

Harry Burton never lived in Stamford after 1895, but he visited and corresponded with family members in Stamford and elsewhere, throughout his life.

They left Barmouth behind around the end of 1896, to live in Italy. Cust was gathering information to expand his interest in Italian Renaissance art history, and was part of the Siena set. Teenager Harry took up photography for Robin’s work. Such was his talent that other art historians became his clients.

Cust began a book about painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi in 1897, which was published in 1906. Many of the well-respected Alinari Brothers’ photos of paintings were used, but also three of Harry’s. The preface gives information about Harry’s social position and work ethics…. traits evident in his later Egyptian times. ‘Finally, I have to thank, with all due appreciation and gratitude, my patient painstaking secretary and companion, Mr. Henry Burton, [sic], whose share of the labour, physical, mental and mechanical, entailed in collecting material and preparing it for the press, has been no light one’.

Robin and Harry were well-known for hosting art and literary gatherings, in their apartment overlooking the Arno on the Via dei Bardi in Florence from 1897 onwards.

Robin met American-born widow Cornelia Octavia Peacock (née Haggerty) in Florence, and they married in London on 25 October 1906. About 1910, Robin and Cornelia moved permanently to Vernon House, 13 Lyndhurst Road, Hampstead. Harry, who spent some time there, often referred to it as the Camden house.

In Florence, Harry became very friendly with American Theodore Davis, who held the concession to excavate in the Valley of the Kings from 1903 to 1914 and Davis took Harry to Egypt. Italy was a stepping stone to Egypt, where the climate only permitted excavation from November to April.

In 1912 Harry became Theo’s Director of Excavations and he worked on the mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu, as well as other sites. Poor health meant Theo gave up his excavation concession in 1914. Theo asked his friend Albert Lythgoe, first Curator of Egyptian Antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to employ Harry. He was assigned to make a thorough photographic recording of the monuments around ancient Thebes, where the Museum Egyptian Expedition had a permanent base. Then he was hired to record the work of the Museum’s

excavation team. Harry now worked for, and was paid by the MMA for about 25 years. Lord Carnarvon, who took over the concession from Davis in 1914, funded Howard Carter, but not Harry Burton.

34 year old Harry married divorcee Minnie Catherine Young, (née Duckett), on 18 July 1914, at Chelsea Registry Office, having met her in Italy, and where they now set up home. On the certificate, he describes himself as ‘archaeologist’. Cust bitterly resented the fact that Harry had made a life for himself working in Egypt and had married a divorcee. He had wanted Harry to give up Egypt, return to London and live like an English gentleman!

From 1916 to 1918, as a volunteer, Harry carried out war work in Cairo, mainly as the Assistant Director of the Re‐registration of Enemy Aliens!

While working for the Met., Harry accidentally stumbled across the Meketre tomb at Deir el Bahri in February 1921. His torchlight picked out the entrance through a crack in the rocks. Herbert Winlock who had been clearing rubble nearby, then took over.

So by 1922 when Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, Harry was an experienced archaeologist and photographer. Howard Carter often used his own photos and watercolour paintings to record his finds, but in his diary for 25 November he writes ‘Noted seals. Made photographic records, which were not, as they afterwards proved, very successful.’ He continued to give detailed daily written accounts. Albert Lythgoe, when asked for the loan of Harry’s services from the Met’s Theban base, willingly agreed. No excavation could take place until photos were taken. Harry later stated that Theo Davis had been only about six feet from discovering Tutankhamun’s tomb when he gave up in 1914!

Even more surprising, the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb on 26 November 1922 was never photographed. Harry Burton started work on 18 December 1922 photographing this so-called ‘untouched’ antechamber of the tomb. In fact it had been open for several weeks, and fitted with electric lighting, mirrors, and other devices to try to get the best photos. For a darkroom, to develop his plates, Harry used a nearby tomb, already a storeroom.

Lord Carnarvon sold the exclusive publishing rights with the photos to the London Times. Harry Burton’s first photographs appeared on 30 January 1923. But Egypt was politically unstable as Britain hadn’t yet given Egypt full independence. Howard Carter also clashed with the authorities on a personal level and closed down his excavations until 1924. Work then continued, Harry meticulously photographing and making notes on all the marvels from the tomb for ten years! The majority of those marvels stayed in Egypt as star exhibits in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum in central Cairo.

Preserved in the Oxford Griffith Institute is Minnie Burton’s diary, dating from 4 May 1922 to 20 October 1926. Among daily records of social and noteworthy events, are notes about the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb. She details such as their Florence life, their stays mainly in Luxor and Cairo, and various European holidays. The Burtons only visited New York once, in 1924. Edward Harkness, a Standard Oil Company millionaire and patron of the Egyptian Expedition funded their cross-country trip to California. He encouraged Harry to visit Hollywood to learn about a motion picture camera for the museum’s work in Egypt. Harry discovered the necessary set-up wasn’t suitable for his work. He later acquired a movie camera, but preferred to use his Sinclair Una camera, either handheld or on a tripod.

While Harry was working on Tut’s tomb, he was also ‘in free time’ doing jobs for the Met’s Theban

Expedition, and being seconded to other people’s excavations! By the late1930s, he had operations for health problems and long periods of recuperation. He also developed diabetes. According to the 1939 Register of 29 September, the Burtons were staying in Seal village, Sevenoaks, Kent. So war had already been declared. They returned to Egypt, as Italy was too unsafe. On 27 June 1940, at the American Mission hospital at Asyut, about midway between Luxor and Cairo, Harry died. Minnie stayed at his bedside until the end. ‘I felt so entirely lost without him’. Harry is buried in the American Cemetery in Asyut.

September 1943 saw allied bombs flatten 25 Via dei Bardi, Florence, destroying any records Harry kept there. Luckily Minnie was still absent.

Harry Burton has left a great legacy. It is estimated he made the Met. 7,500 excavation negatives, 3,345 of Theban monuments and tombs, 1,400 of Tutankhamun excavations, (one set in New York, and a slightly different one in the Oxford Griffith Institute). In Cairo and Italy, there are some 600 of Egyptian antiquities. His correspondence files are at the Met.. Between 1910 and 1940, he recorded over ninety Theban graves!

Harry was known for his modesty, charm, and dry wit, but above all, common sense. An executor for Carter’s Will, Harry advised Howard’s niece Phyllis Walker about a destination for his papers. In the few group photos of him, Harry is usually at the back, dressed in his ‘trademark’ plus fours, (like those of Theo Davis!). He sent expensive presents back to his relatives, and even paid for one nephew to go to Stamford School (until the lad’s father objected and withdrew him!) A niece and another nephew had passed the entrance exams around that time, so proving Harry was a fan of equal opportunities? Amusingly, Harry is said to have ordered British-made suits from Cairo, and they arrived addressed to His Excellency Burton, Tombs of the Kings, Luxor!

Harry’s shots are renowned for their clear tonal, shadowless definition. They tell a story, being much more than clinical scientific records. They are still used today to set up exhibitions which show precisely where objects were found over a century ago.

Harry Burton doesn’t get the credit he deserves. He achieved much more than being known as ‘the man who shot Tutankhamun.’ It is only right that Stamford honoured Harry Burton in June 2022 with a blue plaque on the site of the house of his birth.

© Barbara Midgley

31 January 2023 / 03 February 2023

31 January 2023 / 03 February 2023